Environment: dev.aph.org — Current roles: guest

The Teacher as North Star

The Teacher as North Star

May is Teacher Appreciation Month in the U.S., but here in the museum at the American Printing House for the Blind, we treat every day like teacher appreciation day. Our museum is filled with stories of teachers and their students, applying their ingenuity, creativity, and dedication to the task of advancing literacy and learning. Of course, Anne Sullivan Macy gets the bulk of the press, Helen Keller just called her “Teacher,” but thousands and thousands of other folks have served at historical schools for the blind, public school classrooms, and rehabilitation centers.

Even the best teacher can’t guarantee that every student will succeed. That’s just not the way the world works. But how many young people never get a chance because a good teacher wasn’t there to help them, guide them, inspire them, and, yes, discipline them at that moment when they needed it most? We live in a nation where the shortage of specially trained teachers of the visually impaired continues to be a critical need. We have always needed good teachers, and we still do. When I think about teachers, so many stories come to mind.

Two Brothers, One Purpose

Bryce and Otis Patten were originally from Maine and grew up near Brunswick on the Atlantic coast about 27 miles from Portland. Bryce went to Bowdoin College in Brunswick, graduating in 1837, and his brother, who was blind, went to the Perkins School for the Blind, about 140 miles away in Boston. Soon after he graduated, Bryce moved to Covington, Kentucky, where he taught at a girls’ school. In 1839, he moved to Louisville and opened his own academy, writing to Otis that summer that he had also started teaching a small class of blind students in his apartment for a few hours at night but that, “I hardly know as yet what I shall do with or for them.” I wonder how many teachers felt like that on their first day in the classroom.

(Incidentally, Bryce Patten also noted in that first letter back home from Louisville that, “There is much vice in this place, but little regard is paid to the Sabbath and the Institutions of the Bible.” As Derby Day rolls around, I suppose that also is still true.)

Patten’s plan was to attract his brother to Louisville to help him found a school for children with visual impairments in Kentucky along the lines of the Perkins School, and to do much of the teaching. Of Otis Patten, Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe, the legendary first superintendent at Perkins, wrote, “He is a fine intelligent lad, learns well, behaves still better, and will I doubt not turn out to be a fine practical lad.” As Otis remembered it later, “On the 12th of October 1840, I landed in Louisville inexperienced and a stranger… but with a purpose in my breast… to establish an Institution for the Blind.” When their state-chartered school opened on May 9th, 1842, Otis was the school’s first teacher. He went on to have a full and proud career, became the first head of the Arkansas School for the Blind, and was featured in all of the early national meetings that created curriculum and standards for the fledgling field. He was a “fine practical lad” after all.

A Man of Numbers

This next story doesn’t come from a history book or out of our archives. I learned it sitting in my car with legendary mathematician Dr. Abraham Nemeth and his wife in the backseat. Nemeth was in town to be inducted into the Hall of Fame for Leaders and Legends of the Blindness Field, and as a newly hired staffer at APH, I was sent to pick him up at the airport. Nemeth was a great storyteller, and his wife Edna was, well, patient. Dr. Nemeth told me that from his earliest days, he was in love with math, but that his teachers encouraged him in different directions because the braille code at the time did not have symbols for all of the characters used in advanced mathematical computations. After getting both undergraduate and graduate degrees in Psychology, but still only able to find work in a mailroom, he decided that he could either be an unhappy unemployed psychologist, or a happy unemployed mathematician.

He single-handedly invented a braille math code, published for the first time in 1952, returned to school and received his PhD, and spent a long and fruitful career teaching math and computer science at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan. The way Dr. Nemeth told the story, I have never laughed as long and as hard in my life. You can’t keep a good teacher down.

Teachers Inspire ‘Wonder’

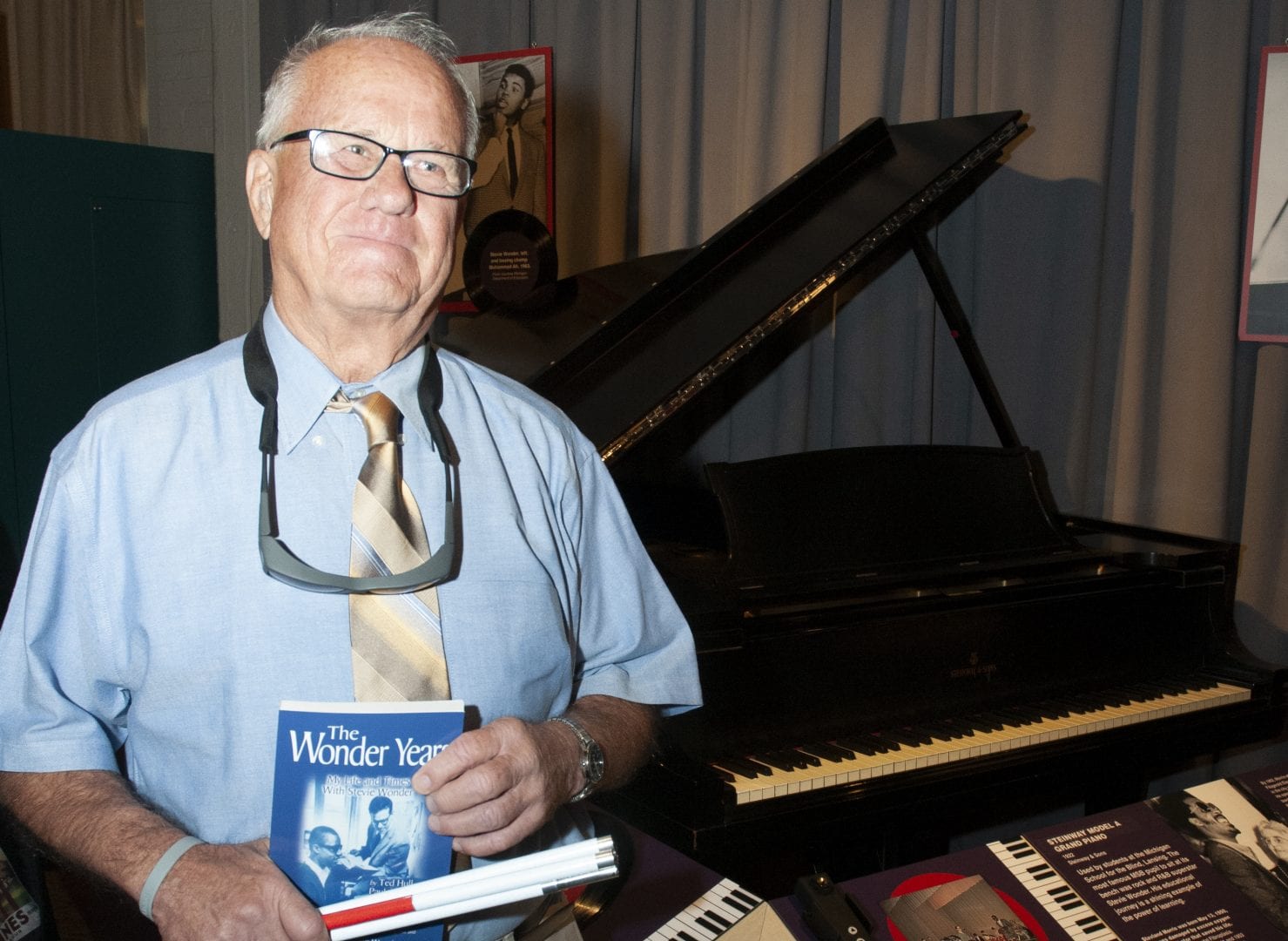

In 1963, a little boy, stage name–Stevie Wonder, had just had a big hit, but his mom and his manager were in trouble with the Detroit school system because they didn’t feel a little boy should be spending so much time touring or in the recording studio instead of attending school. An enterprising Louisville promoter suggested that Motown Records hire a retired teacher from the Kentucky School for the Blind to tutor Little Stevie. Soon, Margaret “Peggy” Traub found herself in an unlikely position on the Motown Review Bus with the likes of Sam Cook and Martha and the Vandellas. That didn’t work out, but Traub connected Motown with the Michigan School for the Blind, who helped the team find Ted Hull, a graduate of MSB and Michigan State University. Ted Hull spent the next six years traveling all over the world with Stevie Wonder, toting their braillewriters and braille books with them everywhere. When the pair weren’t on the road, Stevie Wonder attended MSB like any other student. Ted Hull even ended up writing and publishing a few songs himself! Ted is pictured above in our Museum standing beside a 1922 Steinway Model grand piano from the Michigan School for the Blind that Stevie played during his time there.

I have often wondered what might have happened to Stevie Wonder if he hadn’t found people like Peggy Traub and Ted Hull. What would any of us be without the teachers in our lives? Anne Sullivan Macy helped Helen Keller understand that words have meaning, and Helen Keller went on to use that skill to become one of the most amazing communicators the world has ever known. In each of us, the skills and knowledge our teachers helped us master, they become the tools we return to, again and again, to follow our star.

Share this article.

Related articles

When I started working in the AFB (American Foundation for the Blind) Helen Keller Archive at APH in October of...

Museum objects and their stories are codependent. The artifact is the real deal. After all, it was there when history...